Here’s a Matt Michaels story. One day, years ago, he was lecturing at Wayne State University, a cigarette in one hand, a cup of coffee in the other. As he spoke about jazz theory, the ashes of his cigarette grew perilously long, and the students edged forward, wondering when they would drop. When Matt leaned over an upright piano — look out! — the ashes fell through the open top. He didn’t seem to notice.

A few minutes later, smoke started wafting from inside the piano.

Matt sauntered over, dumped his coffee on the flame, doused it and kept on teaching.

Never missed a beat.

Sing a song of Matt Michaels. Make it sweet and melodic as the best jazz tune, make it funny and smart and a little whimsical, a trill note here or there. Make it smoky and coffee-stained and gently inspiring to anyone who hears it. The old expression goes, “Those who can’t do, teach,” but that is false. Sometimes, those who can do teach anyhow, and the world is better for it.

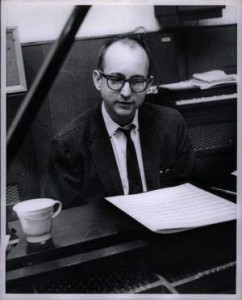

Matt Michaels, 79, may be the most beloved music instructor Detroit ever has known. He could have gone anywhere, recorded anything. He is a master player, a sterling accompanist, a wizard at arranging and writing charts for bands and orchestras. He played with Rosemary Clooney, Peggy Lee, Wes Montgomery, countless others. He helped launch Barbra Streisand and never took it personally when she bolted for New York with his charts.

He taught thousands of future musicians at Wayne State, many of whom now earn far more than their bearded, chain-smoking teacher ever imagined for himself.

But mention his name, and they still bow at his temple. They are here and there, in Detroit and Michigan, in Texas and California and Florida and Europe. And they fondly remember Matt in one of two places: behind a piano or in front of a classroom.

Lately, he hasn’t made either one.

Matt is dying. Thin and gaunt and weary from blasts of chemotherapy, he sat in a bed at Henry Ford West Bloomfield Hospital last week and decided “enough.”

He said to a visitor, “I want to go home.”

Which is where he is now, in Southfield, surrounded by almost everything he loves — his wife, his family, his music playing over a small CD machine.

Only the students are missing.

But when they heard their old teacher was sick, that his long battle with cancer had gone to a minor key, they called and sent photos and chimed in one by one, like a jam session that gets longer and fatter through the night.

Being a Matt Michaels student was an honor, a badge, like being a soldier under the world’s most tender and artistic drill sergeant.

I know. I was lucky enough to be part of that group.

Every student tells a story.

Here are a few of their riffs.

Ken Wlosinski, jazz pianist and composer for TV and film in Los Angeles:

“I was 13 when I started lessons with Matt. He didn’t usually take kids that young, but I was lucky and I loved him.

“Years later, he’d say, ‘Ken Wlosinski. Man. If you want to make it, you really gotta change your name.’

” ‘You think so?’ I said.

” ‘Yeah. How about FRANK Wlosinski?’ ”

Peter Senchuk, an L.A. jazz trombonist who met Michaels as a high school senior:

“We’d be upstairs in the old jazz building at Wayne, sitting at the piano, looking over charts. As a young kid, you always want to come up with an original idea, right?

“So one time I wrote something with a nine-bar bridge. Normally, it’s eight. Matt said, ‘What was your idea here?’ And I said, ‘Well, you know, no one really does that so I wanted to try.’

“He looked over his glasses with his cigarette dangling and said, ‘There’s a reason nobody does that.’ ”

Chris Collins, former student and renowned saxophonist who took over as director of jazz studies at Wayne State after Michaels retired:

“We didn’t get the best facilities in the early days. Back in the ’90s, I was teaching there, and I came in one morning and Matt’s office door had been smashed open. Someone broke in during the night.

” ‘Did they steal anything?’ I asked him.

” ‘Yeah,’ he says, laughing. ‘My Dirt Devil vacuum. Guess that’s the only thing worth taking.’

“The next day I come in — and the other door is broken in!

” ‘What the heck happened?’ I asked.

” ‘You’re not gonna believe this,’ he said. ‘They came back for the attachments.’ ”

Here’s another Matt Michaels story: his own.

Before he taught, he studied. Classical, mostly. A bachelor’s degree at the University of Detroit. A master’s at Wayne. After serving in the Army, he established himself as a top player around Detroit. Caucus Club. London Chop House. Playboy Club.

He was never late. He was never less than stellar. He worked local TV in the days when local TV used house bands and one time, while doing the Channel 4 morning show, an opera singer came in and handed him sheets of handwritten music just minutes before they went on the air.

“More notes than I’ve ever seen,” recalls Dan Pliskow, 76, Matt’s longtime partner on the bass. “Matt had no time to practice it. She started to sing and then she stopped after four bars and said, ‘I can’t do it that high. … Can you take it down a minor third?’

“Matt never said a word, he just modulated down, played the sucker perfectly. It was opera. He had never seen it before. We all just sat and stared at each other.”

That was nearly 50 years ago. Matt Michaels co-founded the jazz studies program at Wayne State, a full-time commitment, yet kept playing until recently, when the cancer made it too difficult. His gigs were like old home weeks for students, who would drop in to say hello or, on occasion, find the honor of sitting in with him. Matt reveled in sharing the stage with those he had taught, and was always generous in backing their solos. He had four children with the first love of his life — his wife, Kaye — and thousands of children with the other love of his life, jazz, children like Christa Grix, a harpist who wheeled her instrument in to Matt for lessons, or Julien Labro, a French-born accordion player for whom Matt created a unique master’s program.

Michaels recorded often with his musical offspring, as well as big local names like his dear friends Dennis Tini, Russ Miller, Jack Brokensha, yet not a single one can ever remember him boasting, preening, losing his temper or even acknowledging his remarkable talent.

Well. Maybe once. The other day, as Matt lay in a bed in his living room, one of his children put on a CD of his music. Groggy from the morphine, Matt still opened his eyes and said, “Who’s that playing?”

Sing a song.

Michael Karloff, pianist, faculty member, University of Windsor:

“One semester, Matt had given me a Chopin Etude to work on my technique. I was more interested in the Bill Evans (jazz) stuff. Being a young punk, I neglected the Chopin for weeks.

“Towards the end of a lesson, when I was working on ‘Autumn Leaves’ or some other jazz standard, Matt says — in his typical dry tone — ‘Oh, have you heard this nice little tune before?’ And he lets loose with a stunning rendition of the Chopin.

“I knew right away I had lots to learn.”

Todd Carlon, pianist and composer for TV and film in L.A.:

“I actually auditioned for Matt the first day at school. I played ‘Some Day My Prince Will Come.’ I was so nervous. But I heard him tell someone, ‘He’s gonna be a good one.’ That meant everything.”

John Sabino, composer and pianist (and my brother-in-law) in L.A.:

“The two biggest influences in my life: The Beatles and Matt Michaels.”

Here’s one more Matt Michaels story.

A student was fumbling. He was frustrated with his playing. Matt popped a sucking candy, made a clucking sound, and said, “Relax. It takes at least two or three weeks to be a jazz musician.”

That student was me. This was years ago. I also have been blessed to know his genius and gentility, and can attest that these stories are not exaggerations. Most kids remember their piano teacher as a stern, glowering force, arms folded, tapping a metronome, maybe writing notes on the sheet music like “Practice!”

Matt Michaels was more like an oracle — a bald, bearded, two-cigarettes-at-the-same-time oracle. His reedy voice was never bitter, his caustic jokes were never mean, and his passion for you and the music you could make was never in question.

It takes a certain belief in youth to see a new kid wandering in through your door, shuffling his feet, hair mussed, eyes lowered, and not think to yourself, “Oh, great.”

Matt never did that. He listened. He gave everyone a shot. Mr. Holland has his opus, and Mr. Chips had his good-bye. Matt Michaels had his coffee klatch and cigarette society and late nights at clubs or buying pizza on road trips and chuckling with pride at the stories his former students brought back to him, like kids seeking an approving smile from their father.

He always gave one.

The other day, at the hospital, he leaned back in his pillow and said, “I have no regrets. It’s been a wonderful party.” And just before he went home, a nurse, following procedure, asked him several mandatory questions. One was, “Do you have thoughts of suicide?”

Matt, ravaged with cancer, thought for a moment. Then he said, “If I did, I’d have eaten the food here.”

Sing a song to Matt Michaels, who sprinkled jazz all over this country. For the handful of former students heard from here, we could have found thousands more. And all the joyful noise they make, every day, is how his melody lingers on, and why his music will never stop.

Leave a Reply